Intestinal microbiota: a fad?

I confess I'm still not sure whether it's a fad or a real revolution...

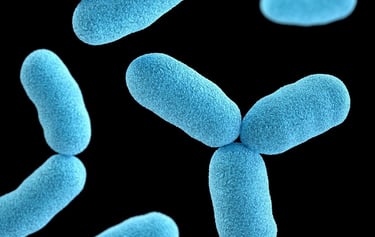

As you probably already know, the intestinal microbiota are the billions of bacteria that live in our intestines and feed on what we eat. In return, they provide us with a host of services: they produce short-chain fatty acids with a range of beneficial effects, they enable the synthesis of certain vitamins, and so on.

Experiments have been carried out to see if and how a change in diet alters the composition of the intestinal microbiota. For example, it was found that switching from a balanced diet to an ultra-processed one impoverishes the microbiota, with fewer families of beneficial bacteria, but also more families of problematic bacteria. When we switch from an ultra-processed diet to a balanced diet, the opposite occurs, and in both cases quite rapidly (on the order of a short week).

It is therefore possible to improve our intestinal health and, through this, our overall health, via the effect on the microbiota of a change in diet, over and above the impact of this change in terms of macronutrient, micronutrient, additives, and chemical intake. This reinforces what we already know: that what we eat has a huge impact on our health.

But there's more to it, and it's now possible to envisage new therapeutic approaches based on interventions on the intestinal microbiota. In concrete terms, it has been shown that a forced modification of the microbiota can cure serious bacterial infections of the digestive system, help to heal psychological disorders such as depression and autism, and reduce the risk of transplant rejection:

People infected with the bacterium clostridium difficile, often as a result of antibiotic treatment that disrupted their immune defenses, precisely via its impact on their intestinal microbiota, have been cured by transferring fecal microbiota from a healthy donor. This is done either by colonization from their anus, or by taking oral capsules of dehydrated fecal microbiota (the FDA authorized the marketing of such capsules in April 2023). It's not very appetizing, but it works, and spectacularly so (within a day).

Similar interventions on people suffering from depression or autism have greatly reduced their symptoms. Remember that intestinal bacteria manufacture neurotransmitters and hormones, among other things, so it's logical that they have a direct link with the brain.

Finally, the transfer of fecal microbiota to chemotherapy patients undergoing transplantation has enabled rejection-free transplants to be carried out, as well as minimizing the side effects of anti-cancer treatment. It has also made it possible to increase the dose and thus the efficacy of the treatment.

Today, a multitude of studies are underway to observe whether such interventions on the intestinal microbiota can have a beneficial effect in other pathologies, such as diabetes, obesity, chronic inflammatory bowel disease, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer's disease. Initial results are encouraging.

Pending more data, I find this logical and not so revolutionary. For me, these approaches amount to forcing the effects of a change in diet, by intervening directly on the intestinal bacteria that this change in diet would produce. I therefore have some reservations about the long-term effects, when the unchanged diet regains its rights over the intestinal microbiota of the person concerned. Time will tell.

To find out more, also read these articles:

On the intestine-brain axis: https://isabellemaesnutrition.com/en/gut-brain

On the links between mental health and food: https://isabellemaesnutrition.com/en/mentalhealth

Bacteria picture by Julien Tromeur